In the heart of every dribble, every swish of the net, and every thunderous dunk lies the heartbeat of a global phenomenon: basketball. It’s a sport that transcends borders, uniting fans in a symphony of action, emotion, and raw athleticism. With over 450 million players worldwide and a fanbase that spans continents, basketball is not just a game; it’s a way of life. From the electric atmosphere of sold-out arenas to the intimate camaraderie of pickup games on neighborhood courts, the passion for basketball knows no bounds.

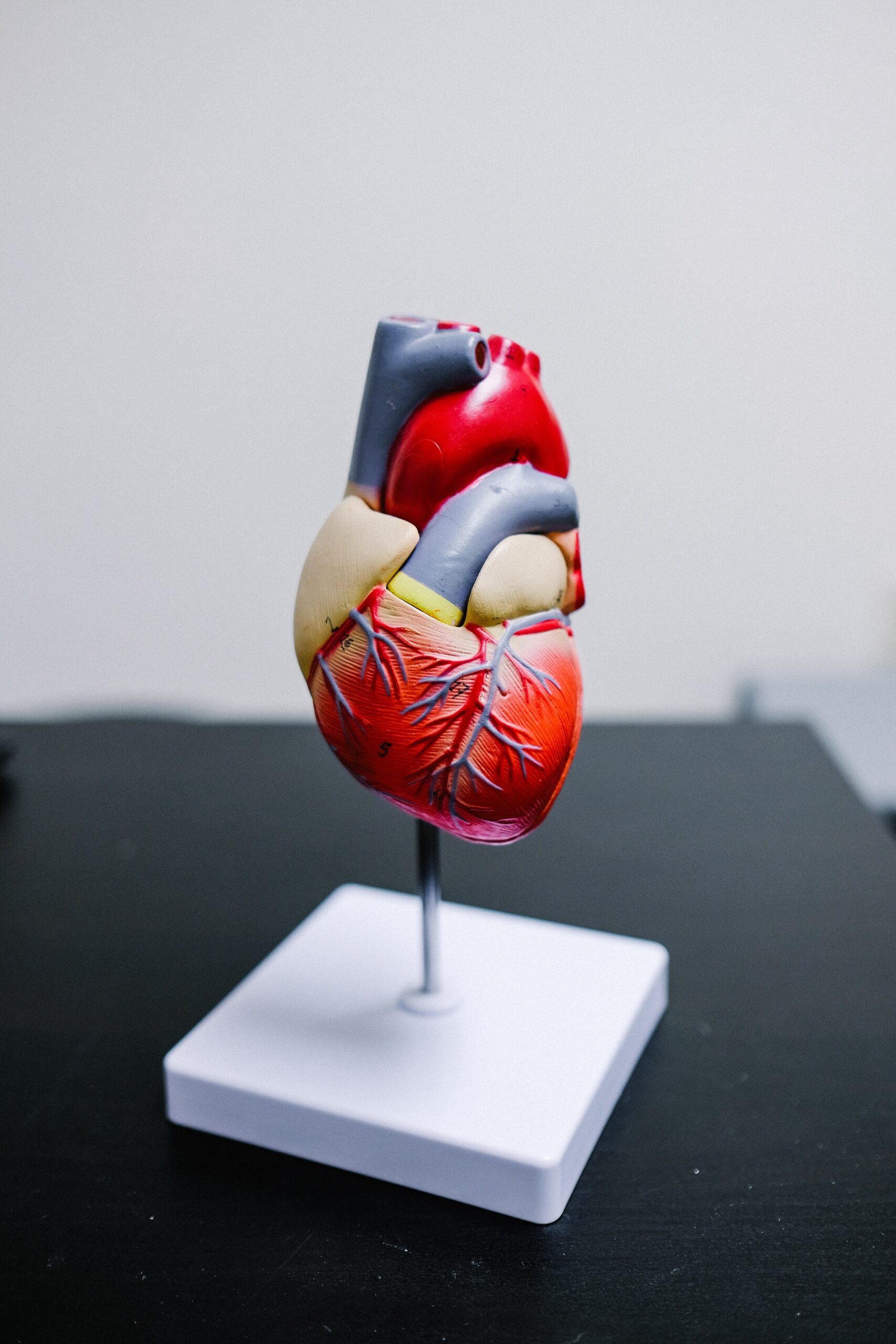

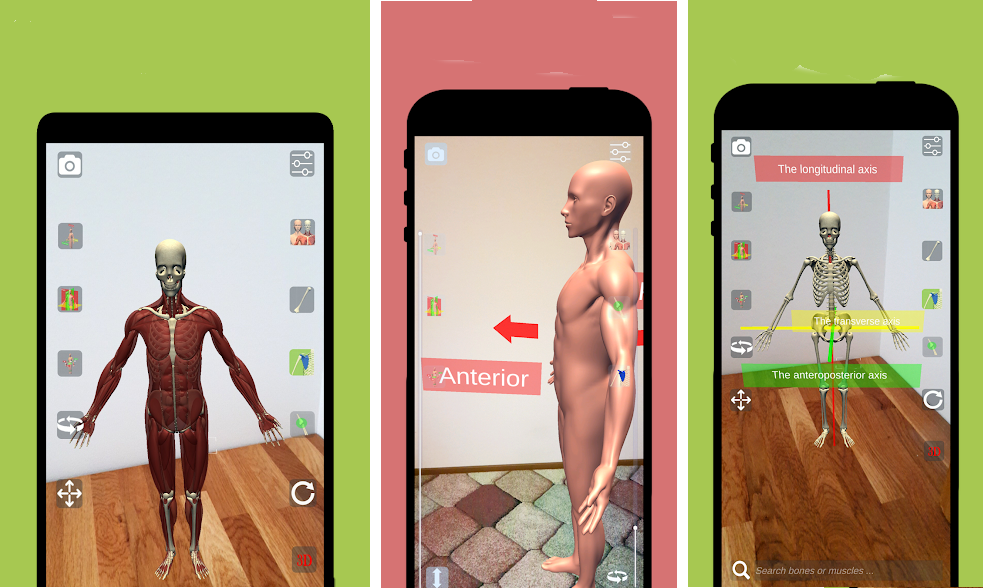

In the pulsating arena of basketball, where every jump shot and defensive block reverberates with the intensity of a thunderclap, the anatomy of the players becomes a symphony of physical prowess and precision. Picture the sinewy muscles tensing as a player drives to the basket, the adrenaline coursing through veins as a defender leaps to swat away a shot, and the thunderous roar of the crowd as the ball finds its mark, igniting a frenzy of emotion. As we delve into the anatomy of basketball players, we uncover the intricate interplay of bones and muscles, the secret ingredients behind every gravity-defying dunk, every pinpoint pass, and every game-changing block. It’s a journey into the inner workings of the athletes who bring the game to life, where science meets passion on the hardwood stage.

Skeletal Strength: The Pillar of Basketball Performance

The skeletal system serves as the framework upon which the entire body is built, providing structure, support, and protection for vital organs and tissues. In basketball, where agility and strength are paramount, the bones play a crucial role in facilitating movement and absorbing impact.

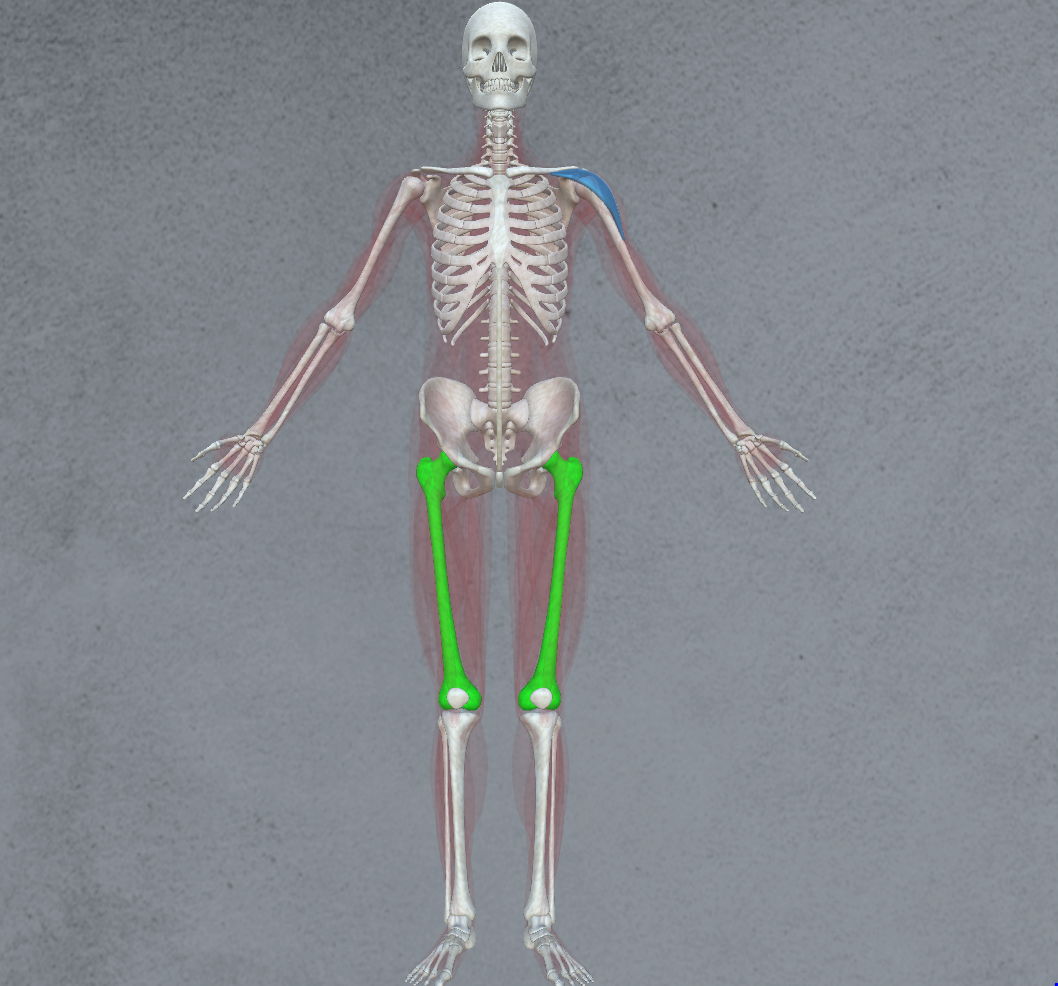

- Lower Extremities:

- Femur: The thigh bone, the longest and strongest bone in the body, forms the foundation for explosive jumps and powerful strides.

- Tibia and Fibula: These bones in the lower leg provide stability and support during running, jumping, and landing, crucial for absorbing the immense forces generated during play.

- Calcaneus: The heel bone, along with the tarsal bones, forms the ankle joint, crucial for balance and stability during quick changes in direction.

- Upper Extremities:

- Humerus, Radius, and Ulna: These bones in the arm provide the strength and leverage necessary for shooting, passing, and dribbling.

- Scapula and Clavicle: The shoulder blades and collarbones provide stability and mobility for overhead movements such as shooting and blocking.

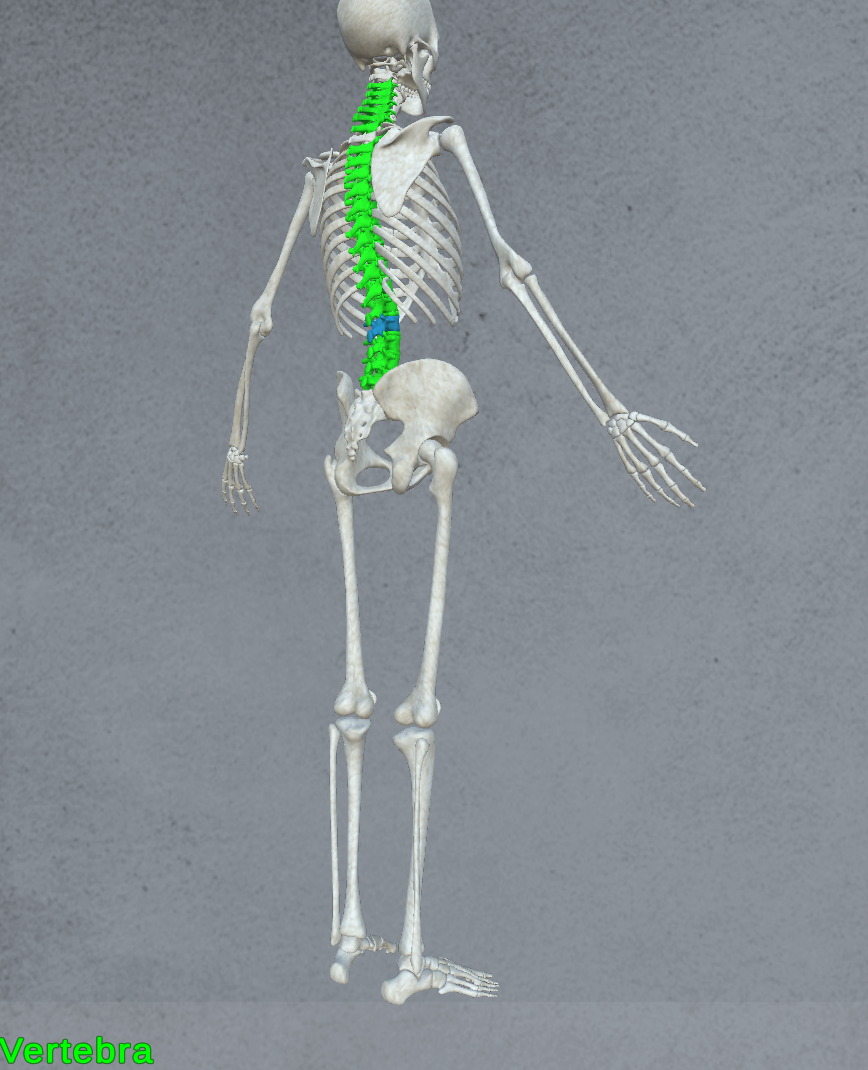

- Core and Spine:

- Vertebrae: The spine, composed of 33 vertebrae, provides support for the entire body and allows for flexibility and rotation crucial for movements like twisting and bending.

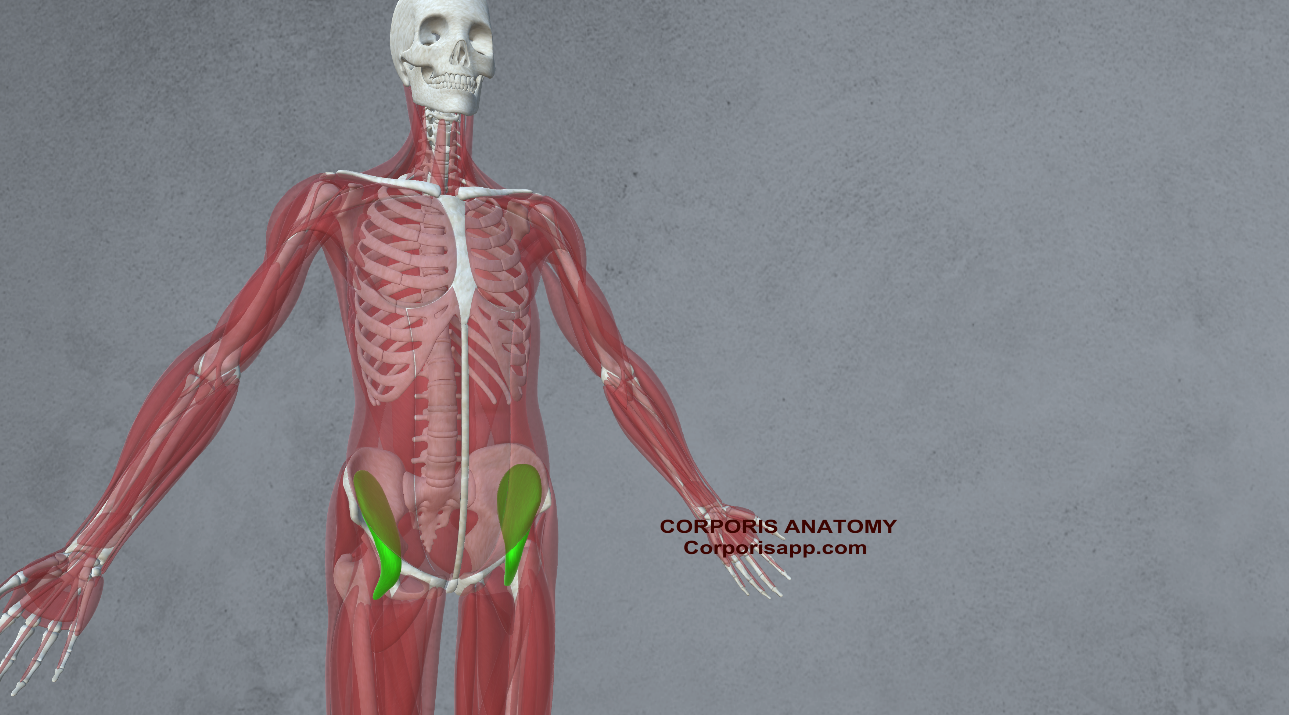

- Pelvis: The pelvic bones support the spine and provide a stable base for the lower extremities, essential for balance and agility on the court.

Muscles: The Engines of Performance

Muscles are the driving force behind every movement in basketball, contracting and relaxing to produce the power and agility necessary for success. Understanding the muscles involved is key to optimizing performance and preventing injury.

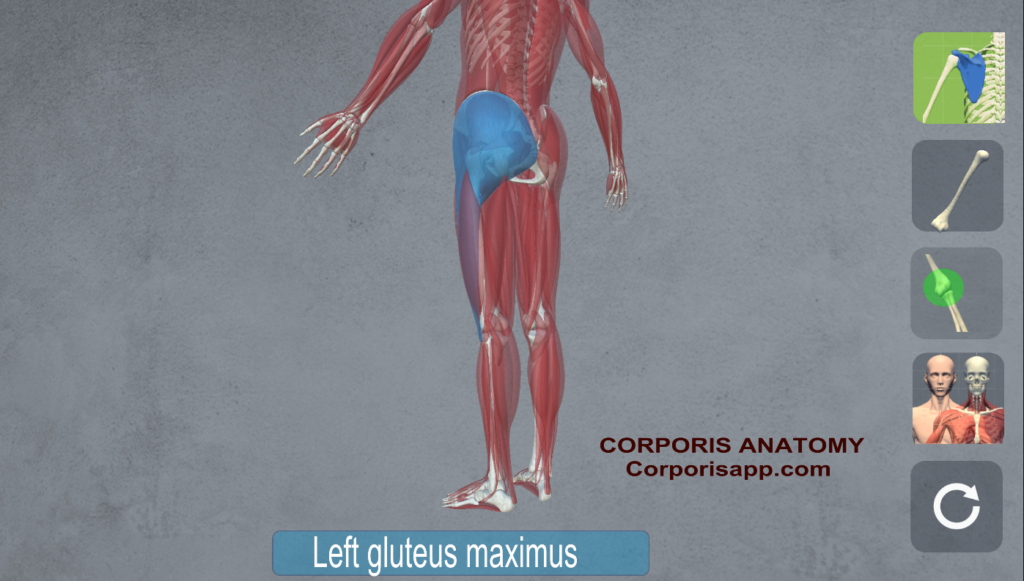

- Lower Body Muscles:

- Quadriceps: Located in the front of the thigh, the quadriceps (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, vastus intermedius) are responsible for extending the knee and powering explosive jumps and sprints.

- Hamstrings: Found at the back of the thigh, the hamstrings flex the knee and extend the hip, essential for deceleration and acceleration on the court (Biceps femoris, Semitendinosus, Semimembranosus)

- Calves: Comprising the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles, the calves provide the strength and propulsion needed for jumping and sprinting.

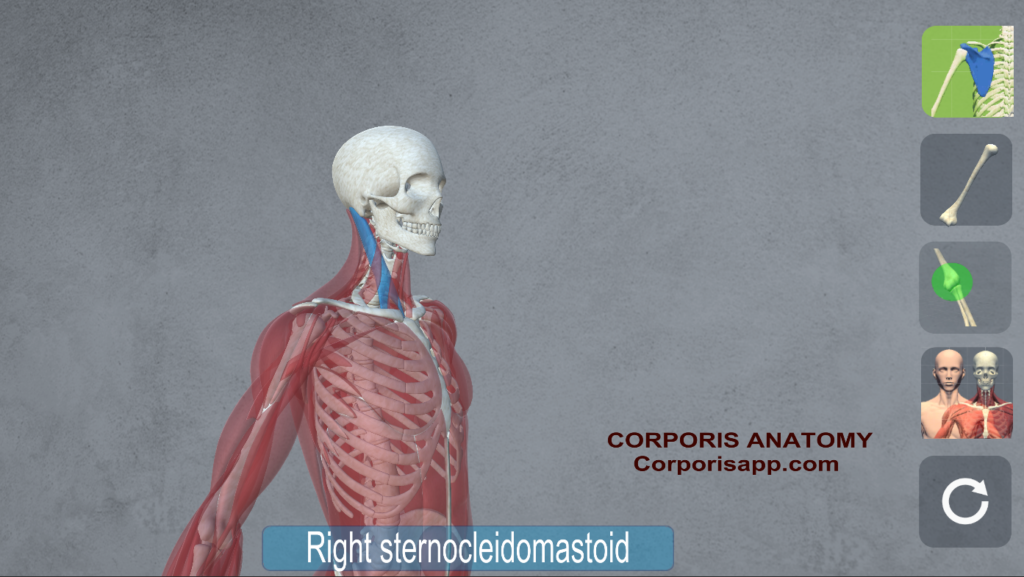

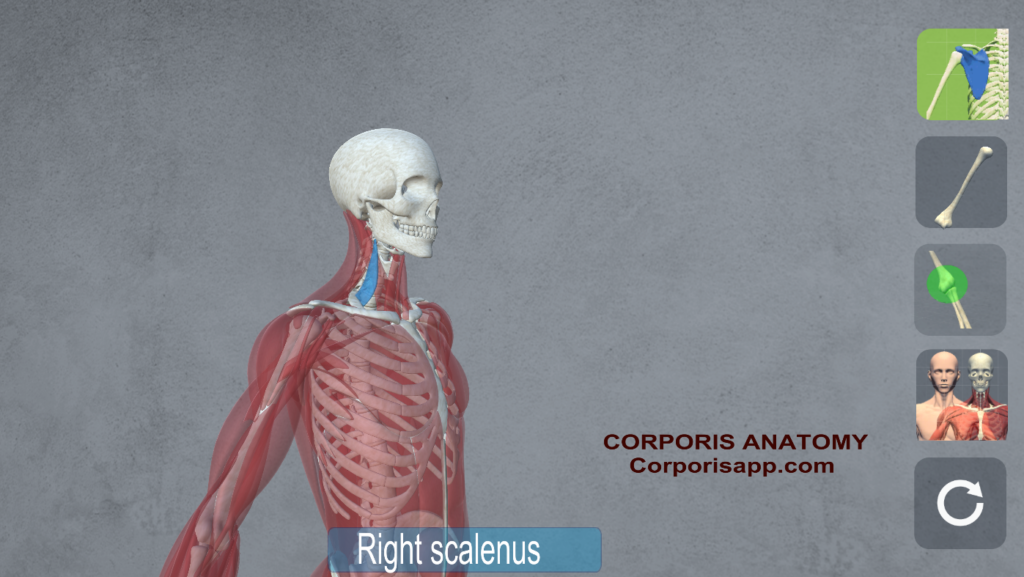

- Upper Body Muscles:

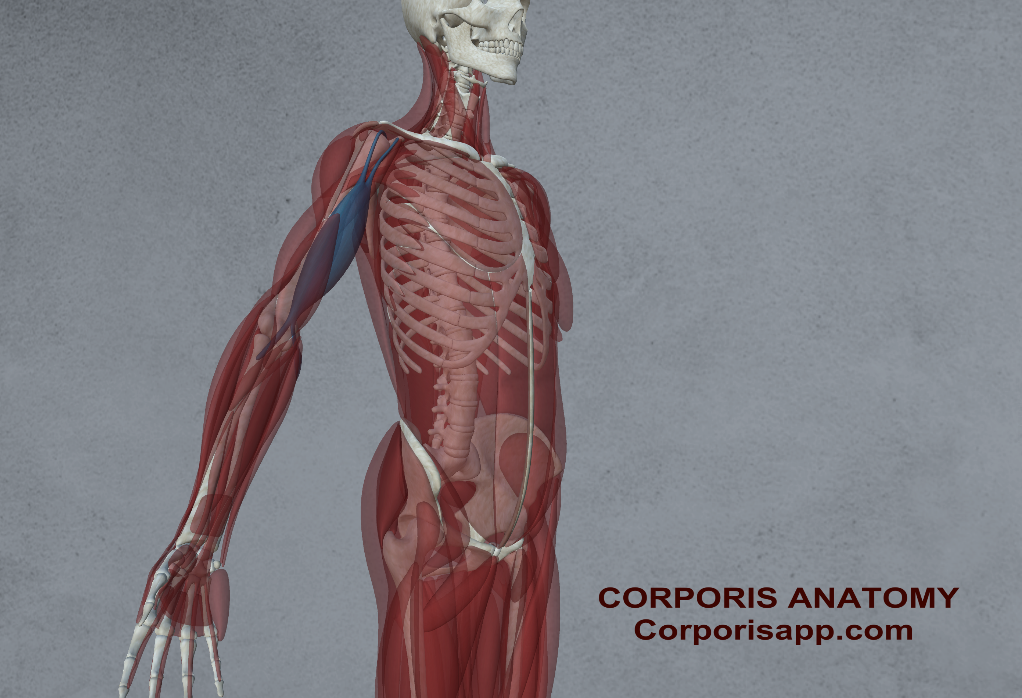

- Deltoids: The shoulder muscles, particularly the anterior deltoid, play a crucial role in overhead movements like shooting and blocking.

- Pectorals: The chest muscles contribute to upper body strength and stability during physical play and contact situations.

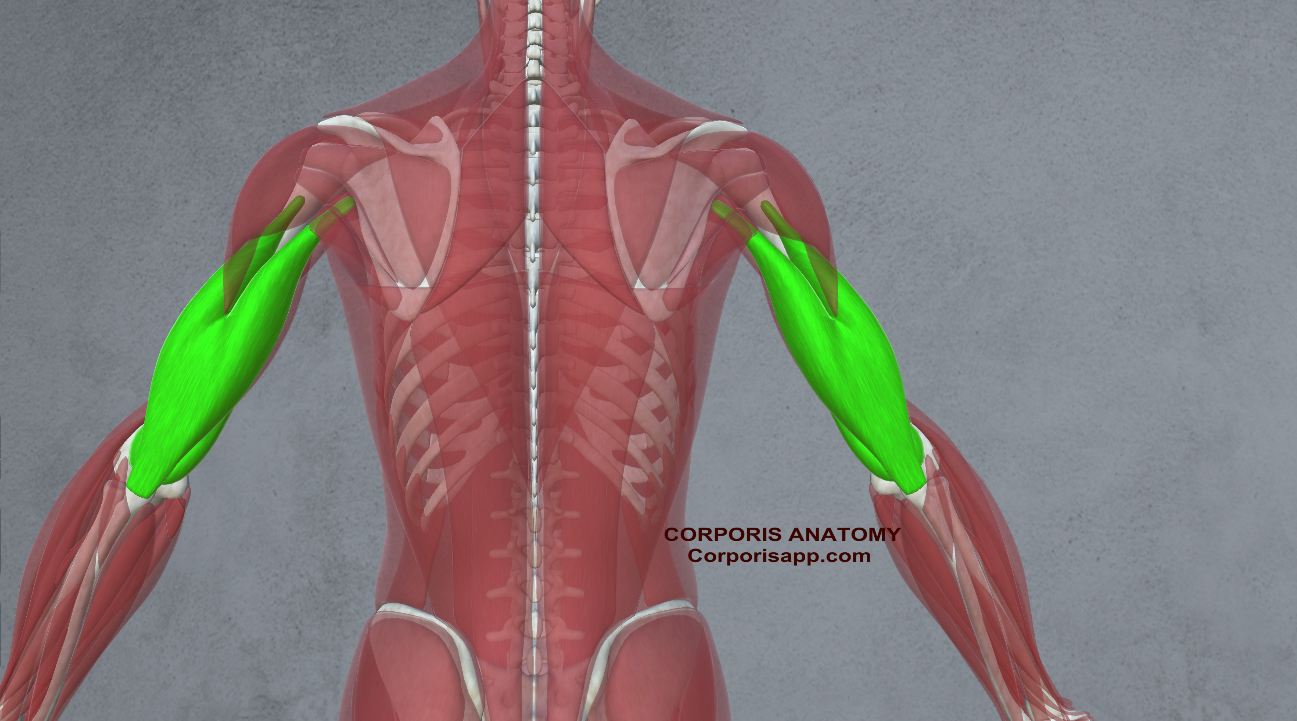

- Triceps and Biceps: These arm muscles are essential for shooting, passing, and dribbling, providing the power and control necessary for precise execution.

| | |

| | |

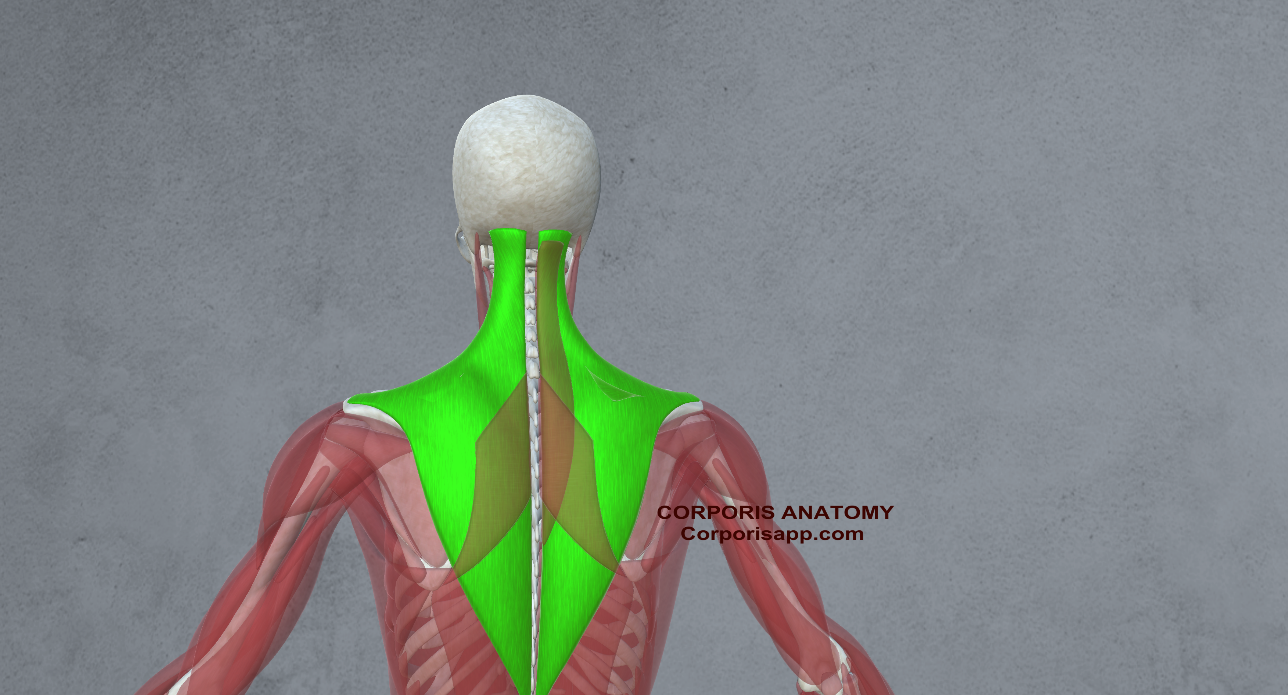

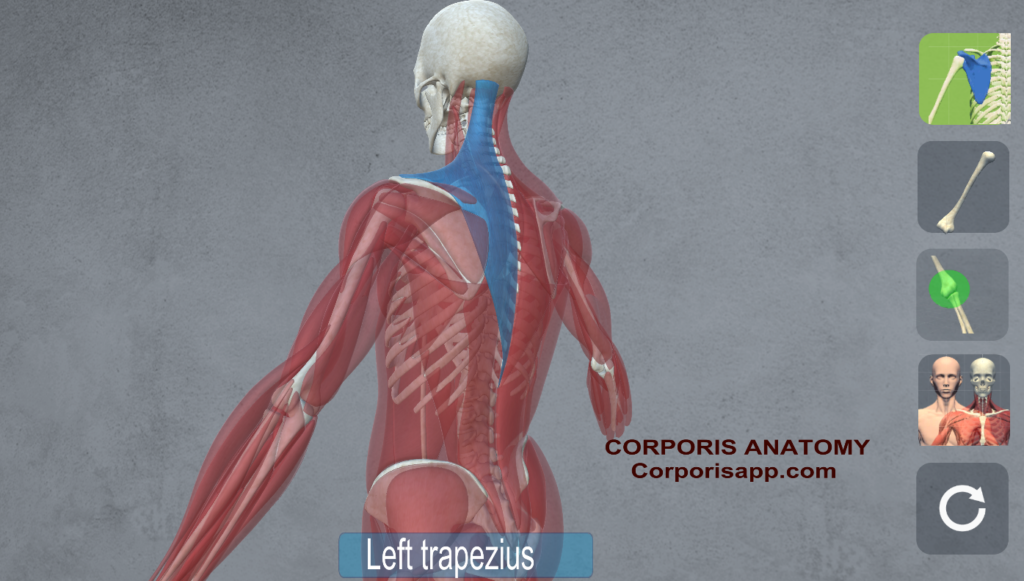

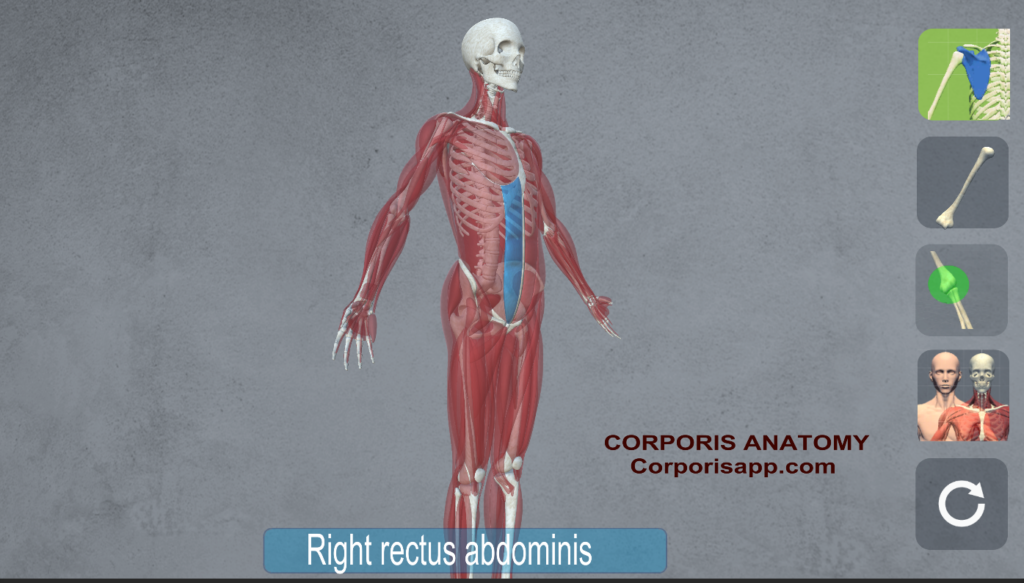

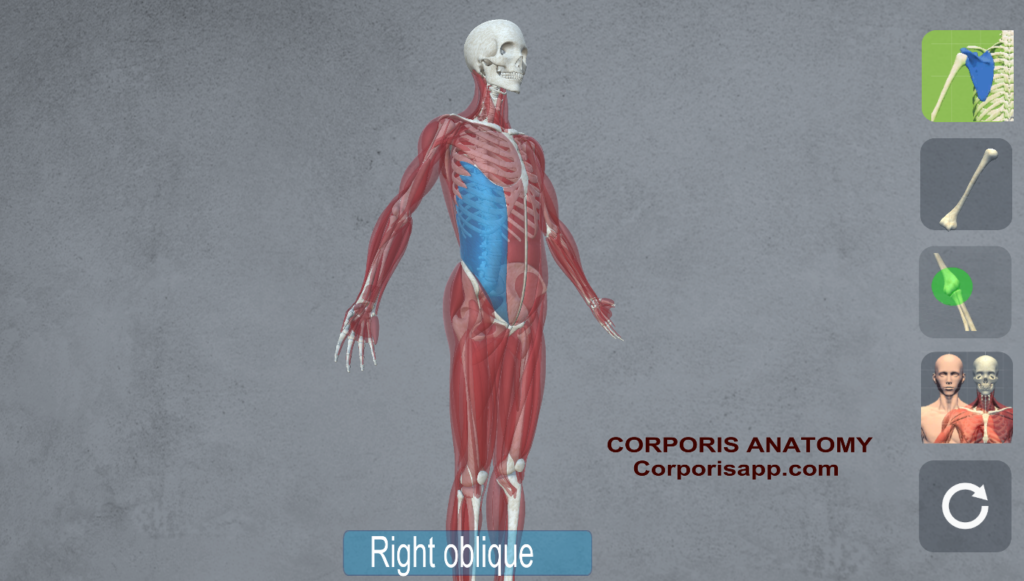

- Core Muscles:

- Rectus Abdominis: The “six-pack” muscles, along with the obliques, provide stability and support for the spine during twisting and bending movements.

- Transverse Abdominis: This deep abdominal muscle acts as a natural corset, stabilizing the core and transferring power between the upper and lower body.

- Erector Spinae: These muscles along the spine help maintain proper posture and alignment, crucial for balance and injury prevention.

| | |

The Integrated System: Coordination and Performance

In the fast-paced and physically demanding environment of basketball, the skeletal and muscular systems work together seamlessly to execute complex movements with precision and power. Coordination between bones and muscles is essential for agility, speed, and strength, allowing players to outmaneuver opponents and perform at their peak.

- Dynamic Movement: Whether driving to the basket, defending against an opponent, or leaping for a rebound, basketball requires a combination of explosive power, agility, and coordination. The bones provide the structural support necessary for these movements, while the muscles generate the force and control the motion.

- Injury Prevention: Proper conditioning and training are essential for maintaining the health and integrity of the skeletal and muscular systems. Strengthening exercises, flexibility training, and injury prevention strategies help reduce the risk of common basketball injuries such as sprains, strains, and fractures.

- Recovery and Rehabilitation: In the event of injury, rehabilitation and recovery play a vital role in returning players to peak performance. Physical therapy, rest, and gradual reintroduction to activity help rebuild strength, mobility, and confidence on the court.

Training

Basketball players engage in a diverse range of exercises and training techniques to develop the physical attributes necessary for success on the court. These exercises typically focus on improving strength, speed, agility, endurance, and basketball-specific skills. Here are some common types of exercises basketball players incorporate into their training regimen:

- Strength Training:

- Compound Exercises: Squats, deadlifts, lunges, and bench presses are foundational exercises that target multiple muscle groups simultaneously, helping to build overall strength and power.

- Isolation Exercises: Specific exercises targeting individual muscle groups, such as bicep curls, tricep extensions, calf raises, and shoulder raises, help address weaknesses and imbalances.

- Core Strengthening: Planks, Russian twists, bicycle crunches, and stability ball exercises are essential for developing core strength and stability, crucial for balance, agility, and injury prevention.

- Plyometric Training:

- Jumping Drills: Box jumps, depth jumps, and vertical jumps improve explosive power and vertical leap, essential for rebounding, shot-blocking, and dunking.

- Agility Drills: Ladder drills, cone drills, and shuttle runs enhance agility, footwork, and quickness, enabling players to change direction rapidly and evade defenders.

- Cardiovascular Conditioning:

- Interval Training: High-intensity interval training (HIIT) involving short bursts of intense activity followed by brief rest periods improves cardiovascular endurance and mimics the stop-and-go nature of basketball.

- Sprinting: Sprint intervals on the court or track improve speed, acceleration, and anaerobic fitness, allowing players to outrun opponents and transition quickly between offense and defense.

- Flexibility and Mobility Work:

- Dynamic Stretching: Leg swings, arm circles, and hip circles increase flexibility and range of motion, reducing the risk of injury during explosive movements.

- Foam Rolling and Mobility Exercises: Foam rolling, yoga, and mobility drills help alleviate muscle tightness and improve joint mobility, enhancing movement efficiency and performance.

- Basketball-Specific Drills:

- Shooting Drills: Shooting from various spots on the court, catch-and-shoot drills, and shooting off the dribble improve shooting accuracy, form, and consistency.

- Ball Handling Drills: Dribbling drills such as crossovers, behind-the-back dribbles, and figure-eight dribbles enhance ball control, coordination, and confidence handling the ball under pressure.

- Defensive Drills: Defensive slides, closeout drills, and one-on-one defensive matchups improve lateral quickness, defensive positioning, and anticipation, essential for shutting down opponents and forcing turnovers.

- Recovery and Regeneration:

- Rest and Sleep: Adequate rest and quality sleep are essential for recovery, muscle repair, and optimal performance.

- Nutrition: Proper nutrition, hydration, and supplementation support muscle recovery, energy levels, and overall health.

- Active Recovery: Light activities such as swimming, cycling, or yoga on rest days promote blood flow, reduce muscle soreness, and aid in recovery.

By incorporating a well-rounded training program that includes strength, plyometric, cardiovascular, flexibility, basketball-specific drills, and recovery strategies, basketball players can develop the physical attributes and skills needed to excel on the court and elevate their game to the next level.

Key Takeaways

- Skeletal Strength is Vital: The bones form the foundation of basketball performance, providing stability and support crucial for explosive jumps and quick directional changes on the court.

- Muscles Power Every Move: Muscles drive every action in basketball, from shooting to defending, requiring strength and agility to excel in the game.

- Key Muscle Groups: Understanding the role of muscles like the quadriceps, hamstrings, deltoids, and core muscles is essential for optimizing performance and preventing injury on the court.

- Contunous Training for Success: Basketball players engage in a variety of exercises targeting strength, agility, cardiovascular fitness, and basketball-specific skills to enhance performance and minimize the risk of injuries, highlighting the dedication and commitment required to excel in the sport

In conclusion, the anatomy of a basketball player is a finely tuned machine, with bones and muscles working in harmony to achieve extraordinary feats of athleticism. Understanding the intricate interplay between these components is essential for maximizing performance, preventing injury, and ensuring long-term success on the court. Through proper training, conditioning, and attention to biomechanics, basketball players can unlock their full potential and excel in one of the most exhilarating sports in the world.

Are you enjoying basketball? What do you find most important when training?